Ali Farka Toure Talking Timbuktu Raritan

Irish Times, June 24, 2005. Times (London, UK), June 11, 1999. Toronto Star, April 23, 2000.

Find a Ali Farka Toure* With Ry Cooder - Talking Timbuktu first pressing or reissue. Complete your Ali Farka Toure* With Ry Cooder collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs.Missing.

Village Voice, May 16, 1989. Washington Post, July 21, 2000. Online 'Ali Farka Toure,' Afropop Worldwide, (October 10, 2005). 'Ali Farka Toure,' All about Jazz, (October 10, 2005). 'Ali Farka Toure,' All Music Guide, (October 10, 2005). 'Ali Farka Toure,' CMJ, (October 10, 2005).

'Ali Farka Toure,' Concerted Efforts, (October 10, 2005). 'Ali Farka Toure,' Nonesuch Records, (October 10, 2005). 'Ali Farka Toure,' World Circuit Records, (October 10, 2005). 'Ali Farka Toure,' World Music Central, (October 10, 2005). Additional information was taken from NPR: National Public Radio, (October 10, 2005).

Ali Farka Toure Singer, guitarist Malian guitarist Ali Farka Toure has often been referred to as a missing link between the blues and traditional music of West Africa. While Toure ’s guitar playing and singing have elements in common with both the blues and traditional African music, that statement is an oversimplification. Ali Farka Toure is actually a mechanic by profession and considers his music secondary. While blues may be a solid foundation for Toure, he has forged a style all his own. Reviewing his album, The Source, Sing Out! Stated that “his right-hand patterns would drive even the most accomplished bluesman screaming into the night and he seems less interested in singing about rambling, gambling, and fooling around than in chronicling the construction of a new irrigation system for the village of Dofana (a project that took him off the road and out of the studio for more than a year). ” Toure is a native of Niafenke, a small village in a remote region of Northern.

The first instrument he learned to play as a child was the single-stringed gurkel, a gourd covered with cowhide and fitted with a neck and rattles. This instrument, which is Toure ’s favorite, has ritual functions; he told Guitar Player, “the sky opens up, and knowledge and power descend on the player. ” However, he also warned that, “it attacks you fast. If you don ’t take certain measures, it can even cause mental illness. Salame Ishq Meri Jaan Mp3 Free Download Songs Pk on this page. ” Toure later taught himself the n ’jarka, a single-string fiddle, and began playing the guitar in 1956 after seeing Guinean guitarist Keita Fodeba.

Understanding Ali Farka Toure ’s music requires an understanding of the differences between his African culture and the culture in which American and European musicians emerge. In some African regions, musical training is passed down from generation to generation among the griots. Author Bill Barlow defines griots as “talented musicians and folklorists designated to be the oral carriers of their people ’s culture Griots preserved the history, traditions, and mores of their respective tribes and kinship groups through songs and stories.

” However, Toure is not a griot, so he is more ambivalent about playing music. He told Guitar Player in 1990, “My family weren ’t griots, so I never got any training. This is a gift I have; doesn ’t give everybody the ability to play an instrument. Music is a spiritual thing-the force of sound comes from the spirit. ” Ali Farka Toure has been performing primarily in public since the late 1970s, when he backed American blues legend John Lee Hooker on a tour of.

He ’s had For the Record Born Ali Farka Toure in 1942 in Niafenke, Mali, Africa; began playing the gurkel (single stringed gourd) and n ’jarka (single stringed fiddle) as a child, c. 1940s; began playing the guitar, c.

Worked as a mechanic; played with John Lee Hooker in, c. 1970s; released albums on French Safari Ambience label, c. 1980s; released first U.S. Album Ali Farka Toure, Mango Records, 1989; toured and collaborated with Ry Cooder, 1994.

Addresses: Record company —Hannibal/Rykodisc, Shetland Park, 27 Congress Street, Salem, MA 01970. Several album releases in before his self-titled American debut. A Village Voice article illustrated the difference between the two guitarists ’ music, “[Toure] doesn ’t crank out one-chord boogies like his idol. It ’s as if he merely hints at the possibility before meandering off in other directions.

” A Guitar Player writer eloquently debunked the “missing link ” hype with the statement, “While Ali Farka Toure ’s song point up the shared lineage of the music of the Mississippi Delta and the African savanna, the explanation for these similarities is not nearly as mysterious as some ethnomusicologists would prefer. Toure, like many other Africans, heard [John Lee] Hooker, Ray Charles, Otis Redding, and others on dance-hall jukeboxes. ” With his 1992 album The Source, Ali Farka Toure began to gain commercial and artistic recognition. It topped the Billboard World Music chart for eleven weeks, helped in part by guest appearances from American bluesman Taj Mahal and guitarist Ry Cooder. In a Billboard profile, Toure ’s manager Nick Gold spoke of the logistics involved with recording him. Ali Farka Toure does not have a telephone, so Gold sends faxes to Mali ’s capital,, which are helicoptered to Toure ’s village. As far as getting other musicians, Gold said it was difficult “because the musicians live in various parts of the north of Mali, and travel is not easy.

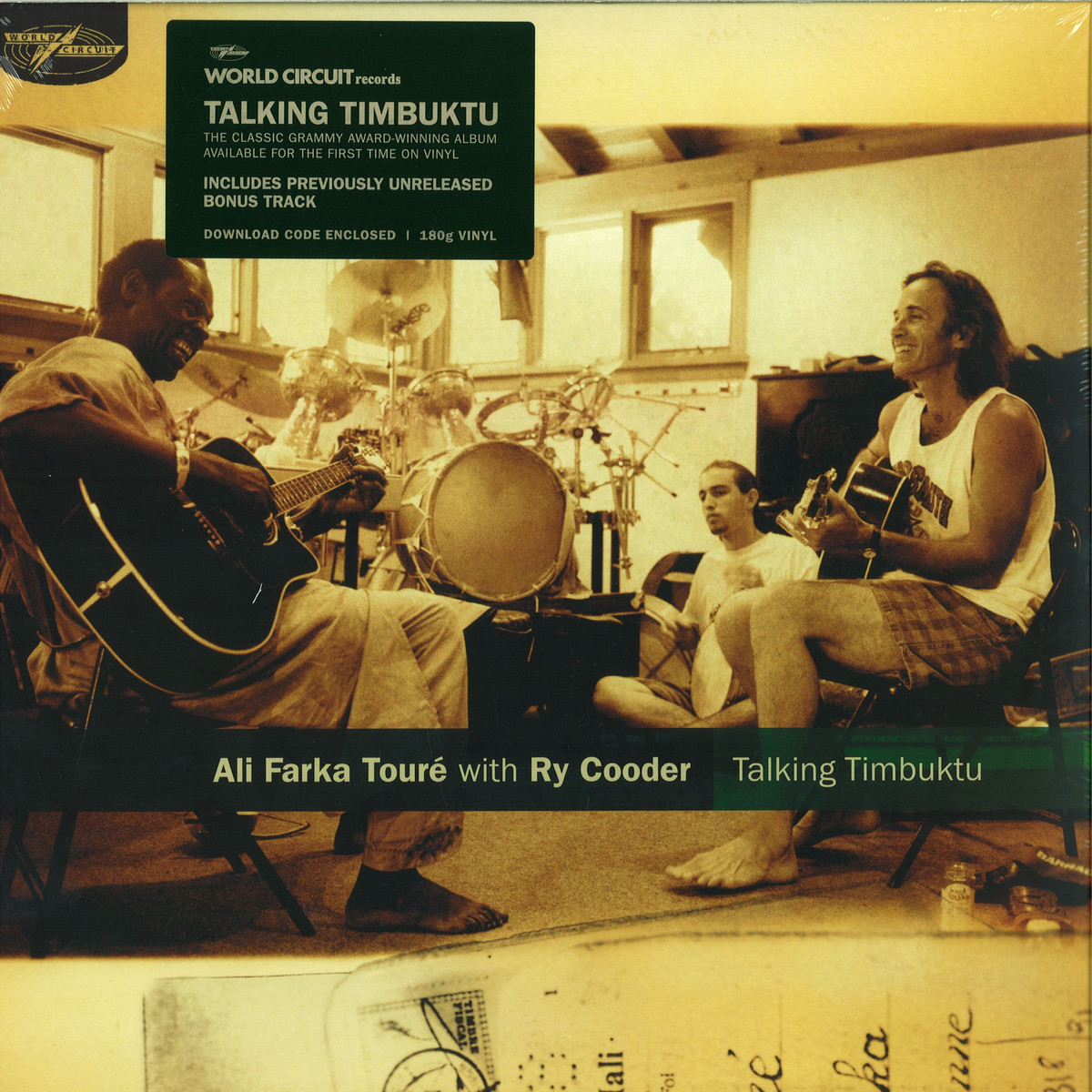

You have to send a messenger out and hope that people will show up. ” During a brief American tour in 1994 with Ry Cooder, the rapport between the two guitarists was such that they completed an album together in four days. The result, Talking Timbuktu, was the 1994 Down Beat Critics ’ Poll ’s “Beyond Album of the Year ” Award. Praised Cooder ’s production on the album: “As a producer, Cooder makes few of the mistakes common to this type of venture. He does not try to alter Toure ’s playing in any way, but takes the songs and builds arrangements around them.

And his guitar playing does not intrude. ” Ry Cooder described the making of Talking Timbuktuto Guitar Player; “You ’d think Ali ’s just goofing and jamming, but they ’re all tunes, because these musicians don ’t jam. Americans do, but Africans don ’t. They don ’t just blow; they play a song.

And he says his melodies are ancient melodies and they have a purpose. ” A typical track from Talking Timbuktu is “Gomni, ” a song about an individual ’s place in the community. Toure describes it in the liner notes, “You have to work hard to achieve a sense of well being. Youshould dedicate your life to the work which brings you happiness.

When the community needs you, you should not turn a blind eye. Every job has its worth and everyone should make their contribution. Ali Farka Toure, Mango, 1989.

African Blues, Shanachie, 1990. The Source, Hannibal, 1992. Talking Timbuktu, Hannibal, 1994.

Bandolobourou, Safari Ambience. Sabou Yerkoy, Safari Ambience. Books Barlow, William, Looking Up At Down: The Emergence of Blues Culture, Temple University Press, 1989. Periodicals Billboard, October 16, 1993; October 30, 1993; July 9, 1994. Down Beat, August 1990; October 1993; August 1994; October 1994.

Guitar Player, August 1990; June 1994. Sing Out!, Volume 38, number 3; Volume 39, number 2.

Village Voice, May 16, 1989. — James Powers.

Talking Timbuktu by with Released March 29, 1994 Recorded Sep 1993 Length 59: 59 with chronology (1993) 1993 Talking Timbuktu (1994) (1996) 1996 Professional ratings Review scores Source Rating Talking Timbuktu is the 1994 collaboration between guitarist and American guitarist/producer. The guitar riff from the song 'Diaraby' was selected for the Geo-quiz segment of PRI-BBC radio program and was retained by popular demand when put to a vote by the listeners. It was awarded a gold certification from the which indicated sales of at least 100,000 copies throughout Europe. Railroad Tycoon 2 Platinum Patch Framingham here. This album features in the book. Track listing [ ] • 'Bonde' – 5:28 • 'Soukora' – 6:05 • 'Gomni' – 7:00 • 'Sega' – 3:10 • 'Amandrai' – 9:22 • 'Lasidan' – 6:06 • 'Keito' – 5:42 • 'Banga' – 2:32 • 'Ai Du' – 7:09 • 'Diaraby' – 7:25 References [ ].